We believe everyone has a right to clean, reliable water, and we want that right to last for future generations. To make this vision more than aspirational, we must protect the land, rivers, and underground aquifers that nourish people and nature and support millions of jobs and countless industries, from agriculture and manufacturing to watershed restoration and recreation.

In California, much like other parts of the western US, groundwater is the sole water source for many communities and wildlife. Yet, when we look at the state of groundwater today, we know things aren’t right.

Groundwater over-pumping is breaking and sinking the land on which thousands of people and families farm, work, and play. It is draining rivers and streams. Shallow wells are drying out, disproportionately affecting low-income communities of color and small farmers who are losing their drinking water and livelihoods.

Meanwhile, the next major drought is looming if it hasn’t returned already. That’s where the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) comes in, offering a platform on which Californians can work together to do more than anyone could do alone and to give the environment and all communities, no matter how much money they have, a better chance at weathering future, harsher droughts.

To make fair and smart decisions through SGMA, California must ensure everyone in a groundwater basin has a meaningful voice in shaping how we protect and conserve our shared water resources. All communities, particularly those without clean, reliable, and affordable water or who rely on shallow water wells, must be able to participate meaningfully in SGMA processes. Local SGMA planning to date has not reflected the full range of communities’ and farmers’ concerns. To achieve SGMA’s vision, we need more and more serious public engagement before it’s too late to prevent groundwater level declines and protect water quality for millions.

Last year, we supported researchers at the University of Vermont and Stanford University to survey hundreds of farmers in Fresno, Madera, and San Luis Obispo counties to understand their perspectives on SGMA, water management practices, and groundwater policy preferences. This work grew from a similar 2017 survey they had conducted in Yolo County with support from the US Department of Agriculture.

While these four counties have geographic, hydrologic, and sociocultural differences, the results of the surveys are similar. Together, they find:

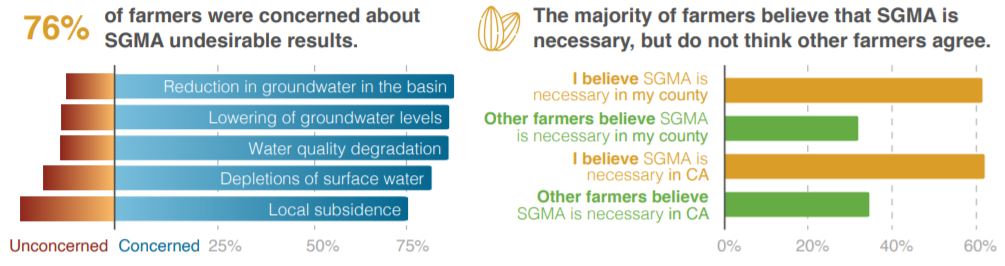

- 76% of farmers were at least somewhat concerned about reduction in groundwater, lowering groundwater levels, water quality degradation, depletions of surface water, and local subsidence;

- most farmers believe that SGMA is necessary but don’t believe that other farmers think the same;

- 71% of farmers agreed that the SGMA process is being managed locally and 68% agreed that it has involved farmers; and

- most farmers are likely to adopt water management practices in the future, including drip irrigation, water monitoring technology, and soil moisture sensors.

Results from surveys on CA farmer perspectives, The University of Vermont Agriculture & Life Sciences.

As state agencies, including the Department of Water Resources and the State Water Resources Control Board, review the first set of local groundwater sustainability plans from critically over-drafted basins and other basins prepare their plans to submit in January 2022, these survey results can help guide next steps.

State agencies and local groundwater sustainability agencies should feel encouraged that farmers agree SGMA is necessary for their counties and for California and that most farmers support water management practices like soil sensors and monitoring. Listening to and understanding these perspectives can help local and state agencies implement SGMA more effectively and equitably.

At the same time, many farmers do not believe their peers feel the same way they do about groundwater management. Given the opportunity to talk more candidly with one another about SGMA and water management, however, farmers could potentially do more to lead on local sustainability efforts.

In the past couple of years, organizations like the California Farm Bureau Federation, the University of California Cooperative Extension, and the Asian Business Institute and Resource Center have started to facilitate these types of conversations and develop materials that help farmers understand and engage on SGMA. Still, more needs to be done.

Other surveys and research support the need for broadening who is represented at the SGMA table. A study by UC Davis found that only 12% of all 260 groundwater sustainability agencies have a board member who represents a small low-income community or independent farmer. The study also found that small-scale immigrant farmers, including Latino, Hmong, and other Southeast Asian farmers, may face language, culture, and land ownership barriers to helping to shape the SGMA processes and plans that will impact their lives.

Community members reliant on groundwater wells also lack representation. Another UC Davis study of small and rural communities’ engagement around SGMA echoed the need for more attention to inclusive decision-making and public participation. Residents reported similar concerns about a lack of accessibility and transparency in Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA) decision-making, as well as a “lack of opportunities to provide meaningful input into decisions or on draft documents” and a “lack of addressing drinking water interests and priorities.”

If done well, SGMA can be a tool to help California enact fair groundwater management that protects current and future generations. However, the first round of local groundwater plans generally do not go far enough to protect our water – for drinking or for farming – in the long term. More public participation in local agencies’ development and implementation of plans needs to happen quickly to fairly consider impacts to farmers, residents, and the environment, particularly as dozens of local agencies begin implementing plans that were submitted this year, and as many dozens more develop the next wave of plans due in 2022.

SGMA should foster decisions based on a diversity of voices and ongoing and rigorous public engagement. It can also enable smart decisions by applying sound science and transparent data. To do this, state and local agencies must listen to, learn from, and respond to the farmers, residents, and places most affected by water stress and scarcity.