Last summer, Norma Bustillos told the Fresno Bee, “It’s kind of scary, you know? One of these days, we’re going to wake up and there’s not going to be water.”

Norma lives in Fairmead, California, where more than a dozen drinking water wells have already dried up in the last few years.

The Union of Concerned Scientists recently created a community guide for the San Joaquin Valley, and a local community organization member in Lamont told the research team: “Climate change is a huge issue. And I guess that’s where the connection with the drought is…and I know it has a huge impact on [agricultural] businesses.”

The Central Valley was once a blanket of wetlands, grasslands, and intermittent streams and estuaries. But over the last century, more than 90% of those ecosystems have disappeared, a slow-moving disaster that has pushed dozens of species into tightening splinters of safe habitat.

With 99% of California abnormally dry, the risks to families like Norma’s, wildlife, and local businesses are ever present. The state’s work under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act to end over-pumping and support local agencies to responsibly manage these shared resources remains urgently important.

With support from the Water Foundation, a collaborative effort among California nonprofits and community groups has been leading statewide advocacy to ensure public agencies and elected officials implement the legislation fairly, effectively, and equitably. This month, the group marked an important milestone.

First-Time Analysis of Local Groundwater Sustainability Plans

Over the past year, researchers and advocates at Ag Innovations, Audubon California, Clean Water Fund, Local Government Commission, The Nature Conservancy, and Union of Concerned Scientists, among others, have been pouring over thousands upon thousands of pages of local groundwater sustainability plans.

While often hard to decipher and full of technical jargon, these plans reveal more about California’s groundwater health than we’ve ever seen publicly available before.

Understanding how well they do or do not pave a sturdy path to sustainability is how residents can know if this public policy is serving public interests – and take steps to hold leaders to account.

Last January kicked off California’s 20-year effort to halt reckless over-pumping. Local agencies in severely over-drafted basins, largely in the San Joaquin Valley, submitted their first plans to achieve groundwater sustainability, including preventing groundwater decline, land subsidence, water contamination, and other requirements. California’s Department of Water Resources is now reviewing those plans to decide if they pass, fail, or need revisions to fulfill those goals.

This month, the team of researchers and advocates released the state’s only analysis to date of Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) implementation that connects environmental justice, public health, and ecosystem health. They analyzed 31 of 46 submitted local groundwater plans for critically over-drafted basins. Their analysis focused on how well each addresses drinking water, climate change, community engagement, and ecosystem health metrics, as defined by the law.

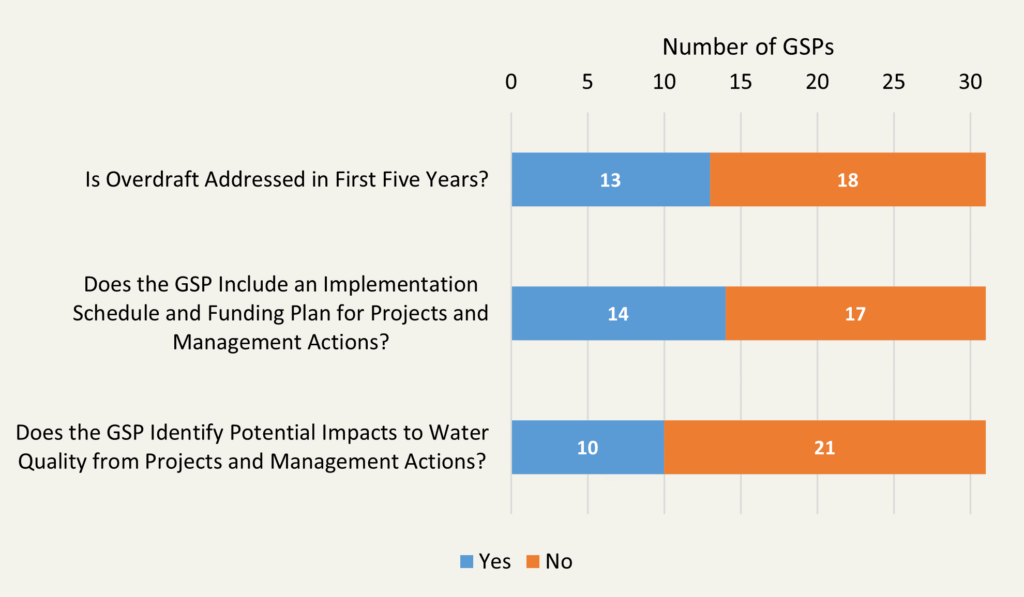

Results from assessment of the projects and management actions in reviewed groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs).

Scorecard Results Call for Greater Attention to Climate Change, Nature, and Community Health

As with any long term change effort, there’s a lot of work to come. These local plans are the first in a multi-year process to achieve statewide groundwater sustainability by 2042. Every five years, local agencies will update and submit new plans, and so these first ones establish the foundation for continued learning and improvement.

While you can find the full results in the group’s summary report, their in-depth analysis highlights where there’s been some progress and where major gaps persist:

- Only 14 plans analyzed how their groundwater management practices and plans will affect communities that are enduring systemic inequity.

- Just 5 plans fully identified wetlands, rivers, streams, estuaries, springs, and vegetation in their basins that rely on groundwater.

- While 30 plans incorporated climate change analysis in some way, just 15 considered multiple climate scenarios. This means that half are not planning for extreme climate scenarios.

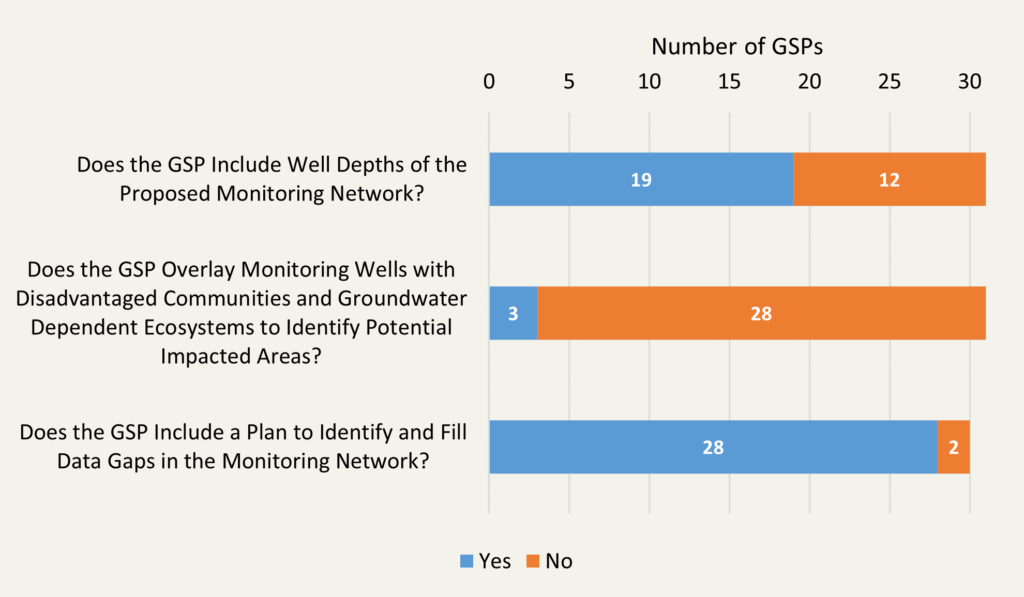

- While 28 plans included how they will identify and fill data gaps in their well monitoring networks, just 3 overlaid those networks with the locations of local communities and ecosystems to demonstrate how they will be impacted by groundwater pumping and management.

- Twelve plans do not identify any projects to stem basin overdraft in their first five years, and only 14 included an implementation schedule and funding plan for how they’ll start making improvements.

Results from assessment of monitoring networks in reviewed groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs).

Making the Grade

As the summary report details, several plans also modeled actions that can help other local agencies learn and improve their plans:

- The Eastern San Joaquin Groundwater Authority plan included detailed maps of community water systems and domestic drinking water wells, as well as the location of communities most vulnerable to over-pumping.

- The Grassland Groundwater Sustainability Agency plan identified all ecosystems that may rely on groundwater, based on guidance from The Nature Conservancy.

- The Northern and Central Delta-Mendota Regions plan transparently details how it developed each water budget scenario and created a projected water budget for baseline, climate change, and with the implementation of projects and management actions.

- The Chowchilla Subbasin plan details how residents were given the opportunity to help shape the plan. Madera County officials worked with Self-Help Enterprises and Leadership Council for Justice and Accountability to inform residents about the plan development process and support their feedback and participation.

- The Madera Subbasin Joint plan responded to feedback from residents and advocates and moved two monitoring wells closer to Fairmead and La Vina communities to help protect more drinking water wells from drying up.

- The Mid-Kaweah plan includes two projects that will monitor wells to evaluate any changes to water quality resulting from groundwater recharge activities.

Engineering geologists with the California Department of Water Resources measure groundwater levels at designated monitoring wells in Yolo County, Kelly M. Grow / California Department of Water Resources.

What’s Next

Through their work over the past year, the team leading local groundwater sustainability plan analysis has helped provide state and local agencies with rigorous analysis and recommendations. State agencies in charge of evaluating plans are considering this analysis, along with comments from others across the state, to inform their decisions.

In January 2022, local agencies throughout the Sacramento Valley and other regions will also submit their first groundwater sustainability plans for over-drafted places. As draft plans are developed this year, our partners will provide their analysis and recommendations to those agencies along with key research materials to aid their plan development.

As the Department of Water Resources makes decisions on this first wave of plans in the coming months, their decisions must create a path to sustainability – and that can only happen through their leadership.

Developing the first wave of plans was exceedingly difficult, so it’s not surprising that many of the plans are lacking. However, the challenges of groundwater sustainability are not an excuse to allow inadequate plans to proceed without necessary corrections and updates. Inadequate plans will harm low-income communities and nature first and worst. Those with the least power should not bear the disproportionate burden of losing their water so that those with the most power can continue over pumping unsustainably.

State agencies have the responsibility to ensure local agencies do better and must be clear about where and how. They can also make this easier by providing guidance and support so that every basin, whether it’s severely or moderately over-drafted, can learn how these first plans missed the mark and create stronger plans that will lead to groundwater sustainability.

Implementing SGMA fairly and effectively won’t be easy, but California can do it if state and local agencies commit to the high standard that our communities and watersheds deserve.