In a recent PBS story about the fight to clean up toxic tap water in California’s San Joaquin Valley, residents in the Valley and a lawyer from Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability remembered a meeting with a local city official who asked, if the water is so bad why don’t you move somewhere else?

In the story, Lucy Hernandez, a community leader and water activist from Tulare County, asks back, “how is that going to fix the problem by me leaving? Then, what’s going to happen to the community? There’s not going to be a community, and there’s not going to be a community for you to represent. So you’re going to be without a job. Because who are you going to represent? I’m the community. My house is not the community. I’m the community.”

Who ensures everyone has clean, reliable water? Who protects the rivers, streams, lakes, and aquifers that create and sustain life? Who wields power and authority over water and whose interests do they serve?

Every day, a maze of local, state, and federal agencies and officials make decisions about water. Their deliberations determine whether and how people have safe and affordable drinking water, neighborhoods are protected from flood and drought, rivers keep flowing, and much more.

Yet, across the United States today water systems, public agencies, and regulators are not prioritizing clean water for everyone. A quick survey of recent reports finds: Two million people in the US are denied basic plumbing and running water. More than 1.5 million households across just 12 cities have been charged over $1 billion in water debt. Nearly 8 million homes and businesses face significant risk of flooding that the Federal Emergency Management Administration’s models don’t acknowledge.

This didn’t happen by accident or for unknown reasons. Systemic inequities and racist policies lie at the root of every major US water challenge, including US denial of Tribal rights, redlining and racist zoning ordinances, and disparate impacts of flooding. For every outcome mentioned above, these and other unjust water policies and practices have harmed the lives of Black, Latinx and Indigenous communities and low-income communities at greater rates than for anyone else. Right now, these decisions are making it even harder for communities of color to protect themselves during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The San Joaquin Valley city official who did not feel responsibility to help constituents get clean water and stay in their homes is not an outlier in a governance system predominantly built and led by white people. A 2011 study found that water utility leadership was 94% male and 96% white. In their recent report, H2Equity: Rebuilding a Fair System of Water Services for America, Sridhar Vedachalam, Timothy Male, and Lynn Broaddus say, “we see little evidence that the 8,000 utilities that serve the majority of the population are moving toward strongly diversified boards of directors, elected bodies, or general manager positions…This lack of diversity hampers the utility’s understanding [of] its diverse customers’ needs and changing priorities for service improvements.”

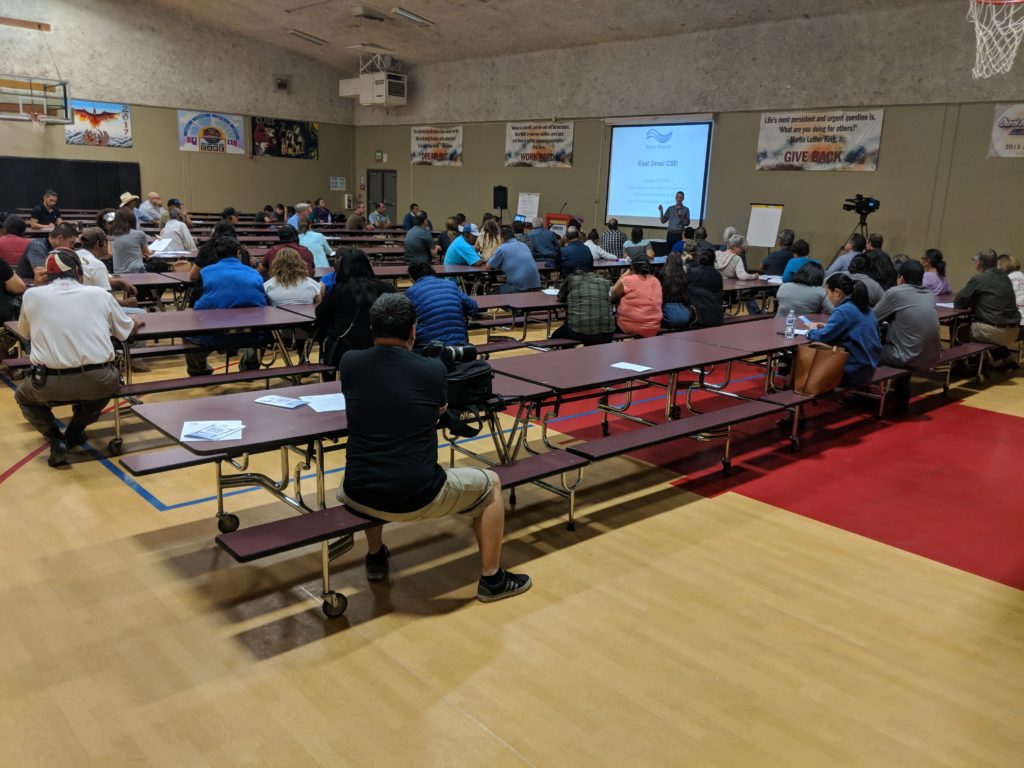

In East Orosi, CA, community members attend a public meeting on water system consolidation, Community Water Center.

This extends to many water boards too, which are responsible for overseeing the delivery of safe water, setting water prices, and communicating with the public. For example, research by the Community Water Center in 2018 found that while 65% of southern San Joaquin residents are Latino, just 15% of local water board members were Latino. That same study found that during a 4-year period, 87% of 565 local water board elections were uncontested. The Southern San Joaquin Valley also happens to be the center of a decades-long epidemic of unhealthy and expensive drinking water, fueled in part by groundwater over-pumping that is drying up rivers, streams, and riparian habitats and causing land subsidence. Improving the situation for communities that have been denied safe, affordable, and reliable water will not happen until they are represented in water leadership and decision-making.

At the Water Foundation, we believe that when local and state decision makers represent the full priorities and aspirations of their constituents, we will see more public resources allocated to those communities’ real needs. When communities’ experiences and ideas are treated as authoritative expertise, we will see smarter public water policy that produces multiple community, environmental, and economic benefits simultaneously, such as well-paid jobs, resilience to climate change, clean air, green open space, and more. When communities feel meaningful investment in their security and prosperity, we will see greater civic engagement that produces leaders and decision-making representative of and responsive to that community’s goals.

Visitors at the Pacoima Wash Natural Park in San Fernando, CA, which includes trails, picnic areas, and green infrastructure that captures and filters stormwater, Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority.

Over the next few months, we’ll be digging more into this vision and sharing the insights and ideas of leaders and organizations working every day to enact a systemic shift in water democracy and governance in order to achieve outcomes that benefit all people and nature. We’ll also dive more into what funders can do to support the organizing, advocacy, and political work necessary to alter power relationships, undo inequitable water policies, and build a functional and representative democracy.

To get started, check out a recent post on the need for broader, more inclusive decision-making in sustainable groundwater management and an interview with Melissa Bahmanpour, a Southeast Los Angeles elementary school teacher who also leads River In Action. Melissa also serves on a local steering committee to help oversee LA County’s new green stormwater capture program.