As part of an ongoing series on broadening who makes water decisions and how, we’re exploring the role of water boards.

2022 ushers in another round of important elections: midterm elections at the federal level, and much farther down ballot, local elections. Races to decide who serves on water boards — often opaquely named ‘community services districts’ or ‘public utility districts’ — get little notice. Yet local water leaders can have a huge impact on our daily lives. For instance, in California, local water leaders make the critical decision about whether to shut off people’s water due to nonpayment or to accept state and federal funding to forgive customer debt. They also decide whether to raise customer rates, apply for grants, or allow water infrastructure to fall into disrepair.

Can you name a local water district leader or even the entity that provides your water?

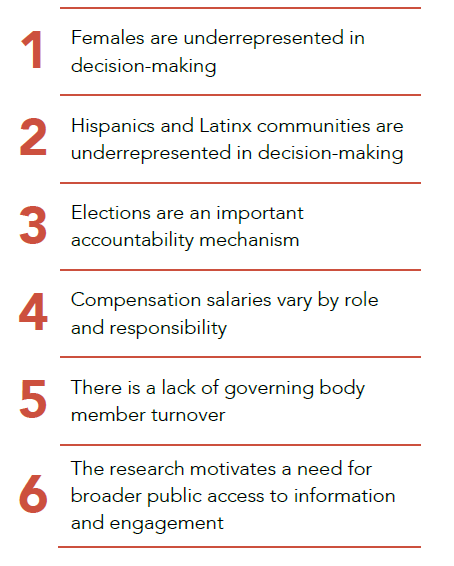

Despite the direct impact on communities, it is very challenging to figure out who makes decisions about your water. Last year, we asked UCLA’s Luskin Center to look into water governance in Los Angeles County. Their research found that water governance in LA is like many other places: unrepresentative of the communities served (in terms of gender and ethnicity), stagnant (board members spend over a decade in office, on average), and non-transparent (with 40% not holding public meetings and less than a quarter providing translated materials).

Credit: UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation

To address the pervasive lack of transparency in water governance, UCLA just launched the Los Angeles County Water Governance Mapping Tool. For the first time, information about the leaders of retail water systems in LA County is easily searchable. You can enter in any address and find out the:

- Name of the water system that supplies water to the address

- Names of board members who direct the policies of that water system

- Demographics, tenure, and pay of individual board members

- Methods for selecting board members, including eligibility and election cycles

- Average cost and relative affordability of water from the system

- Safety and quality of water from the system

- Water operator qualifications

- And more

Easy access to this information allows community members to advocate for their needs — and potentially to move into decision-making roles themselves.

Community-centric water leadership

Credit: Laurie Jones Neighbors, Cities & People Advisors

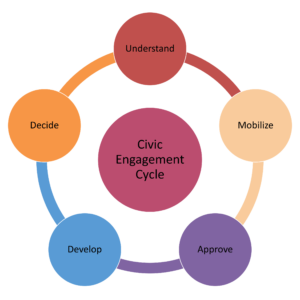

According to Laurie Jones Neighbors at Cities & People Advisors, realizing community-centric water leadership takes investment in each phase of the civic engagement cycle, including supporting communities to:

Understand: Recognize local, systemic inequities in water access, quality, cost, and infrastructure and know how local public decisions about water are made.

Mobilize: Act in coordinated, large numbers with a unified vision of water equity to shift public attention while putting pressure on decision-makers to ensure that policies and initiatives reflect community priorities.

Approve: Participate at the invitation of local decision-makers in public planning processes that vet or reject policies and projects put forth for adoption by those inside governance.

Develop: Collaborate among themselves and with insiders to create programs and policies related to water equity, drawing on social and technical expertise.

Decide: Hold key decision-making positions in water governance, including elected office (such as on water boards) and appointed seats (such as on planning commissions) and get recruited and prioritized for staff positions that manage water access, quality, and infrastructure. (Laurie Jones Neighbors, 2021)

While there are a number of community-based organizations making major strides in some of these phases, only a limited number have been able to support community members to play significant roles in water leadership and decision making. This is a key missing link. Thus, the Luskin Center team worked closely with a community advisory committee to ensure that the online mapping tool provides community members with information important to them about local water leadership, and is accessible to as wide an audience as possible.

Three members of the community advisory committee, East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, Physicians for Social Responsibility – Los Angeles, and River in Action provided ongoing feedback throughout the development of the mapping tool. Working in close partnership with community organizations and their members brought a wide range of perspectives, experiences, and needs that informed the design process and has been important to increasing the transparency of water system governance and data.

The community partnership does not end here. The Luskin Center plans to update the water system data in the mapping tool regularly and respond to further community feedback as community members spend time navigating the dynamic functions of the map. If you have ideas or suggestions, please email the Luskin Center here.